< Blog Home Page

Is é Seo Mo Scéal Agus Táim Ag Fanúint Leis

For the Feirtears, no doubt those years of famine, and the longer decades of poverty and degradation came enshrouded in grief and loss. Beyond that there was the family. For twenty generations perched at the tip of the peninsula, itself on the edge of the island, on a windswept and sometimes harsh landscape, a landscape possessed of a raw grandeur and sweeping beauty. Home.

Home. From Mount Brandon, westward down to the sea, along the rocky shore, with the small coves and harbors, and for some centuries the abandoned fortress, once the family’s seat and symbol of power. All lost, yet lingering in memory as an echo, replete with names and memories of some small greatness – Eoghan, Muiris, Eamon - names of vanished Feirtearaigh, or Ferriter chieftains, yet still given to the babies of the family at birth, generation to generation. And then the glory of Piaras Feirtear, the last Irish Chieftain to surrender to the English, martyred at the hands of the Cromwellians – only memories.

What do we know now of the lives of these people – tenants of Lord Ossory and of Lord Ventry going into the period of the Great Famine? While the 15th century may have been a time of prosperity and even of joy for the Irish of Corca Dhuibhne, the times thereafter offer a spectacle of gradual and sometimes sudden decline – for the area, and for the fortunes of the Feirtear family.

When the great Lord FizGerald, Earl of Desmond, went to war against the crown in defense of his prerogatives as the Palatine Lord of South Munster, the Feirtear Family must have been in his service, at least at the beginning. That the Feirtears would bear arms in Desmond’s service extends from the enfiefment granted by the FitzGeralds of the lands inhabited by the family since the Norman incursion. As the fortunes of the FitzGeralds of Munster waned, so did the fortunes of the Feirtears. Despite efforts to remain aloof from the final act of Desmond’s fall, at the close of the 16th the family was of much reduced circumstances.

The two great wars fought in Ireland during the 1600s, first the Cromwellian War, and finally the Jacobean War completed the denouement of the old Irish, and of the Hiberno-Norman families who did not renounce Catholicism. In each of these conflicts, Feirtears fought on the Irish Catholic side and lost both times. How many male members of the family left with the 10,000 who followed Sarsfield to Europe after the Treaty of Limerick was signed, we do not know. That any Feirtears who remained on what had been family lands were poverty stricken and largely dispossessed is certain.

The Catholic tenant population in Ireland following the Jacobean defeat lived lives of grinding poverty and unrelenting misery, this we know. Introduction of the potato as a food staple allowed population to increase, as the amount of land required to support life diminished with this crop. Tenant plots became smaller and smaller with each succeeding generation.

Excerpt from a description of his tour in Ireland by Gustave de Beaumont (1830s):

"Imagine four walls of dried mud (which the rain, as it falls, easily restores to its primitive condition) having for its roof a little straw or some sods, for its chimney a hole cut in the roof, or very frequently the door through which alone the smoke finds an issue. A single apartment contains father, mother, children and sometimes a grandfather and a grandmother; there is no furniture in the wretched hovel; a single bed of straw serves the entire family.

Five or six half-naked children may be seen crouched near a miserable fire, the ashes of which cover a few potatoes, the sole nourishment of the family. In the midst of all lies a dirty pig, the only thriving inhabitant of the place, for he lives in filth. The presence of a pig in an Irish hovel may at first seem an indication of misery; on the contrary, it is a sign of comparative comfort. Indigence is still more extreme in a hovel where no pig is found... I have just described the dwelling of the Irish farmer or agricultural laborer."

And one might wonder why anyone stayed. Home. So, many did leave, in singles and in small groups. Fathers hoping to later bring their wives and children, bereft wives with children, in search of men since departed, since vanished. Men, women and children – across Ireland, in their millions, and of these millions, some dozens of Feirtears. Lost from home, forever.

Some came to Boston, some to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston, and New Orleans. All great entry points for the Irish. Some were sent to Quebec, and some died in the coffin ships outside Grosse Isle, at the port of Quebec. The Ferriter name is there, carved into the memorial along with thousands of others.

The Gaelic inscription reads: "Children of the Gael died in their thousands on this island having fled from the laws of the foreign tyrants and an artificial famine in the years 1847-48. God's loyal blessing upon them. Let this monument be a token to their name and honour from the Gaels of America. God Save Ireland."

At that time, and for decades thereafter, Irish Ferriters left their homeland for America. Once ashore, and recovered from travel, these men and women struck out, in the manner of the times, to establish themselves in the new land. During the early years, from the 1830s to the 1860s, most were barely literate, if literate at all, and most spoke Irish as their first language. So off they went, in the company of other immigrants, at least some of whom spoke their language. If not family, at least countrymen. Off to the mills of New England and New York, to the mines of Pennsylvania, to the docks of Baltimore, Charleston, and New Orleans.

We – that would be us, the followers in time, the successors, have pieced together some of the travels, some of the pathways taken by our lost and scattered ancestors. From the forests of Maine, the mills of Massachusetts, the dark and dangerous coal mines of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Illinois, some found safe have westward on farmlands in Illinois, Iowa, and Nebraska. Onward - westward to the mines of Montana, and to the shimmering possibilities of California. Within a succeeding generation or two, Ferriters are appearing in positions with the railroads, as lawyers, as politicians, and as people of property, on the land.

For most of these people, up until the dawn of the next century, the 20th, there would be little contact with other Ferriter family groups, save for when by chance there might have been settlement in the same town. Many Ferriters settled in the factory areas of the Connecticut River Valley, from Hartford up through Springfield, and Brattleboro Vermont. Surely some of these people knew of one another, and as successive waves of immigrants arrived, renewed a certain familial sense. Not so for most, scattered afar, and out of touch, clinging to their Catholic faith, and with a sense of their past, but with no knowledge of their lost kin.

For six generations, the earliest Ferriter Immigrants have lived this way. Sometimes in the same cities with cousins they knew nothing of. The tiny families and small kinship groups that formed after the Diaspora, grew, and in a few case became extended families in their own right: witness the Farritors of the Nebraska Prairies, who struggled and prospered, now numbering in some dozens of families, or the famous Butte Ferriters, hardrock miners who have been a feature of the Montana landscape now for generations.

With each wave of emigration, a greater possibility of retaining contact with extended families existed, sometimes seized, sometimes not. With the coming of the 20th century, the means for reliable and consistent communication with the homeland came to be, and at last the terror and grief of immigration was relieved. Irish Ferriters arriving after 1900 often kept in touch with those back in Ireland, and brought over relatives when circumstances permitted. For these people, an active contact with Kerry and the villages of the Dingle Peninsula has often been sustained.

The 21st Century has arrived, and with it, easy and commonly accessible means to communicate across vast distance and to locate people virtually anywhere have come into being. Seven generations after the first great wave of emigration, and after the first exodus from the family’s Irish Homeland, Ferriter Family members have the ability to consider where the collective experience of their ancestors have taken them, and to take sure and certain steps to understand the relationships that have all along existed between their families, and other families who share the same name.

The fact that we have Farritors, Ferreters, Ferritors and Ferriters is incidental. These spelling variants are accidents of translation, bureaucratic mistakes, and pronunciation – nothing more. Like some Irish who use the Irish spelling, Feirtear or Feiritear, and the Anglicized version Ferriter interchangeably, the choice exists to honor the past by sustaining the spelling that has been given, but also to freely accept that this is, in fact one family.

That the past not be forgotten, for the summary of the lives of all of those who have gone before us sums up to form the ground of experience upon which we tread. From Sybil Head to Grand Isle, to the mines, the mills, and the factories of the Americas, and thence to where the Ferriter Family stands today. All a part of one thing.

Archived comments:

michele said...

Great essay, George!!! In a few words some Historians have used...it is also called, THE IRISH EMPIRE.

3 August 2008 14:19

Know Your Ancestors

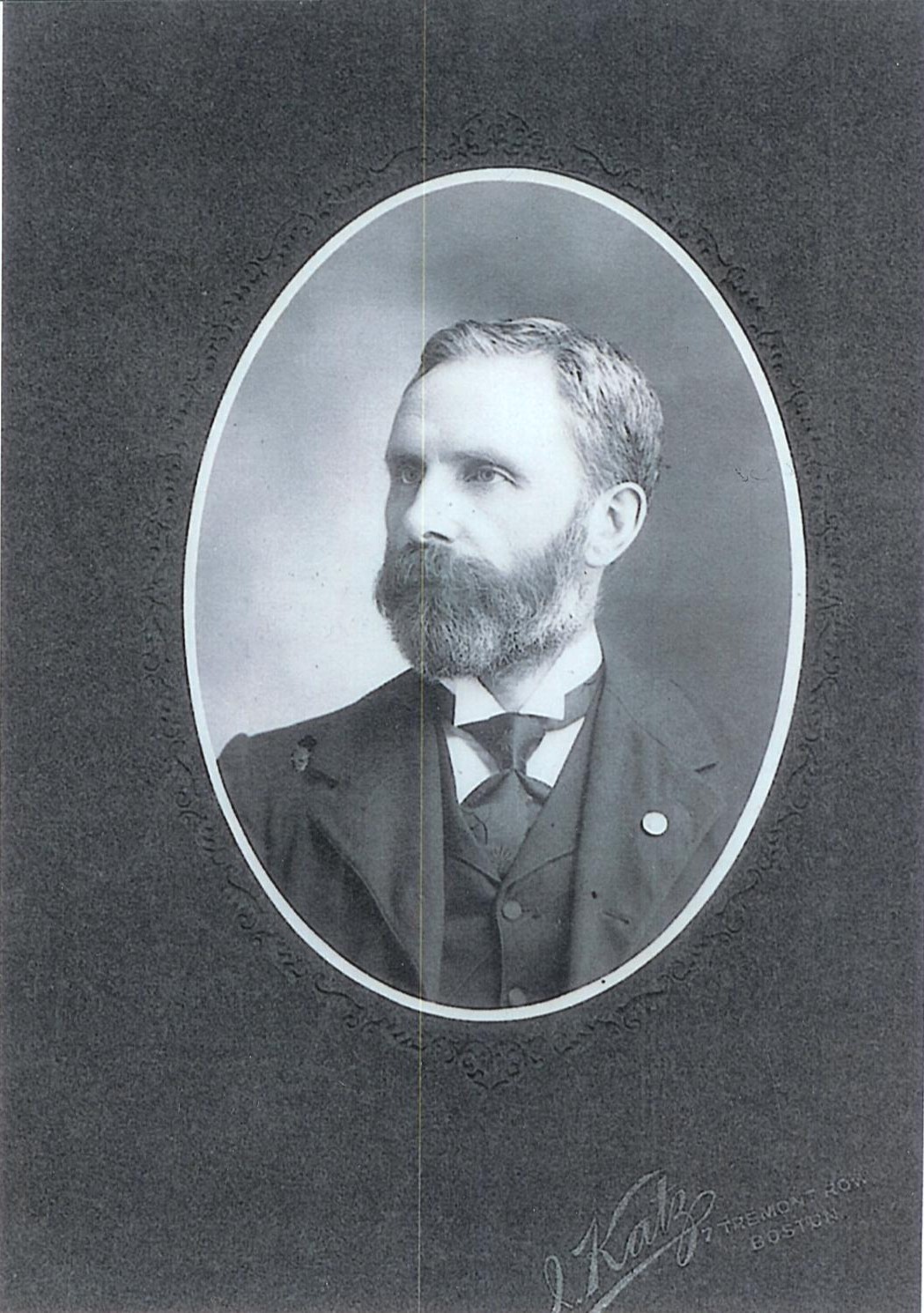

Padraig Ferriter

Padraig Feiritear was born 8 March 1856 to Maurice Ferriter and his wife, Nell Mhichil Mhainnnin at An Baile Uachtarach near Bally Ferriter. He was the fourth of nine children. His father, Maurice was a successful carter and farmer, a tenant of the Ventry family. Educated by the Nation School System of the era, he also studied Latin and Irish. Mostly self-educated in Irish, he displayed an Academic knowledge of the Language. He devised his own system of writing Irish. As a young man, Padraig began replicating (copying by hand) Irish manuscripts made available to him by local families. He also interviewed local families and... Read More