< Blog Home Page

A Brief Summary, and Directions to be Taken

Creation of the new Ferriter Family website moved me to a review of certain items that I had in hand, for inclusion on the site. A number of these are now posted as blog entries, including the following. None of these observations, speculations, and theories have been altered by the time that has passed between having been written and now…enjoy reading, and comment, please!

I have been exploring the very early and early period of Ferriter Family activity in Ireland, with a goal of illuminating aspects of our common history in that place.

The principal source for early references has been the various Calendars that exist. These Calendars are summary abstracts of various legal documents and court records extending forward from the earliest period of the English conquest in Ireland.

There are several types of these Calendars, each relating to a different type of “roll”, or official record. There exist Calendars of Plea Rolls, Justiciary Records, State Papers, Chancery, Exchequer, and Ecclesiastical Rolls. Since the original documents (the rolls themselves) were in some cases later destroyed (mostly by fire – the Four Courts fire in 1922 was not the only fire), the Calendars are invaluable source material.

While it is very clear that Paul MacCotter did a wonderful research job, and before him, Father Michael Manning, and historian Thomas Westropp, an absolutely thorough investigation is not yet complete. While I will summarize in general terms what I am doing, it is important to keep in mind that there are document collections that have never been cataloged or calendared, and that while well preserved (mostly) are not yet explored.

As I have previously noted, quite a bit of the source material has been placed on-line. Google, the British Archives, and a number of other “free source” efforts have digitized a lot of material. Where I have not found something available in full text on-line, I have found on-line guidance to library locations, or purchase points. I am doubly fortunate to live within easy driving distance of the University of Wisconsin Memorial Library, which is a world – class repository.

So, what have I learned? Probably not much more than we already knew, but there certainly have been some tantalizing suggestions as to which way to go for greater enlightenment!

Ferriters arrived in Ireland as Le Furetur, in the second generation following the initial Anglo-Norman intrusion. This early reference comes from the “Liber Niger Alani” , or The Black Book of Alan, which is ecclesiastical in nature. In this citation, both a Walter and a William are identified, with the Walter deceased, but having held property then left to his son William. This suggests that Walter was established as a Episcopal tenant on the Manor of Swords (near Dublin).

Within a very short time (perhaps two years), we find another Walter le Furetur in Kerry. For the next several decades, there are parallel citations appearing in the sources involving the family both in or near Dublin, and in West Kerry, in Ossurys Cantred, which includes Dunurlan, Marhin, and Dunquin. Within a generation, the lands long noted as associated with the Ferriter Family appear increasingly as being held by Ferriters.

Having become familiar with Paul MacCotter’s work, you will know that the early Ferriter Chiefs (family heads) filled the socio-economic niche of “knight of the shire”. In this capacity they held lands in return for various types of rent from the liege lord. There are a number of source documents that show le Fureter/le Fereter (the name is used interchangeably, sometimes within the same document) as being as being of knightly rank – serving on Juries, having liberty of the gallows, and holding sizeable tracts of sub-tenanted land.

On the various entries on the rolls, the name Ferriter (in its several variations), appears alongside the names FitzGerald, Trant, Hussey, Cantillon, Barry, and others, all names that figure largely in the history of Munster, and some of whom became large and powerful families as time progressed.

There are on the order of 15 discrete citations found for the period 1240 – 1300, with perhaps 10 in the period 1300 – 1380 and only a half-dozen or so covering the period from 1380 – 1550. I am not fixing hard numbers because I am not finished yet, but this is how it is shaping up. That’s only 30 or so informational artifacts coving three hundred years of time, and over half of those fall within the first century. There are about twenty different names involved, with three exceptions they are men.

I have reason to regard the earliest Walter le Furetur as the “prototypical Ferriter”, or the first immigrant (possibly the only immigrant).

I also have developed a pretty keen appreciation as to why the frequency of citations falls off. The principal reasons are the falling away of central authority, and the associated “hibernicization” of the Norman families, coupled with the eventual destruction of the House of Desmond in the 1570s. Since I am now aware of how much data was brought forward by the House of Ormond, I can only realize that it mimics what was lost when Desmond fell, and all of the abbeys, monasteries and strong houses were destroyed, along with their contents. As I pointed out before, the Four Courts fire in 1922 was certainly a tragedy, but thanks to the activities of the “calendarists”, we have some data. What was lost with the Desmonds can only be imagined.

I have come across some very intriguing things associated with the Nicholas Ferriter of the late 1300s. He probably was a hero of some sort, although the details of his deeds long ago went up in smoke. There is just enough of an outline, just a hint of a shadow as cast by this man such that I am continuing on with a focus specifically on this one individual.

Of that, more later.

There is a grand history here – one of struggle, success, decline, and adventure. The tale has two parts: this first coming to a close amidst bloodshed, chaos and loss, with the second still playing out.

And of that, also more later.

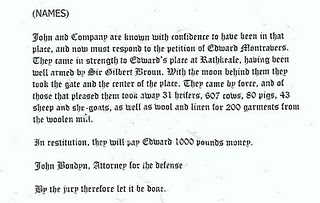

TÁIN BÓ 1335

Cattle Raid

The following is a story from the life of Nicholas Fyreter, a man who lived during the middle years of the 14th century in Ireland. The episode as presented is accurate in terms of the historical context and the central event – aligning the very scanty documentary references to this Nicholas with the historical framework has provided the structure for recounting the tale. That this Nicholas was the son of the better documented family chief Philip le Fureter junior, or that this Nicholas himself became family chief are both conjectural, but both are supported by facts. The main event and the names of those involved are a part of the historical record.

Some background is necessary to place this story in context: The military, social, and economic consequences of the Norman Incursion dominated most of Ireland in 1335. Only at the geographic edges – northwest, west and southwest – those areas that had felt the Norman fist in passing, or where successful push-back had occurred did the ancient Irish system remain more or less intact. Where Norman or English Lords had not been able to sit or to remain seated life proceeded as before – everywhere else English Law held sway and intermittent warfare between the marcher lords, or between the newcomers and the native Irish sputtered and flared, broken only by periods of uneasy truces and periods of exhaustion.

During the early years of the Norman incursion, and in areas closely controlled by the invaders, vigorous efforts were made to establish and maintain English law. During this period, activities such as cattle-raiding and hostage taking were suppressed, although these practices continued unabated in Irish controlled areas. The native Irish also made a practice of raiding into the English controlled areas, taking away hostages and plunder, in their traditional manner of warfare.

As the 14th century progressed, central control and the power of English Law began slipping away, beginning in the outermost territories beyond the Pale. The Normans farthest from the locus of control began to Hibernicize, and Irish traditions, speech and culture reemerged. The Desmond FitzGeralds, in their several lordships, followed this pattern. Despite being made an Earl in 1328, Maurice FitzGerald, the First Earl of Desmond was a part of this trend.

An accelerating slide into anarchy within the marches was marked by the murder of William de Burgo, the Brown Earl of Ulster in 1333. That he had been struck down by several of his liegemen signaled a loosening of feudal grip. Ulster and Connaught moved farther away from the reach of English Law, and the Irish chiefs and petty kings once again held sway. Cadet lines of the de Burgos across Galway and Mayo became “Burke” and practiced all manner of Irishry, as they would continue to do so until Elizabethan times. In Munster, the newly created first Earl of Desmond, Maurice FitzGerald, was first made Earl (1328), then quickly imprisoned (1331) for making unsanctioned war. As the power of English Law continued retreating, cattle-raiding- sustained in practice within the Irish controlled areas - was taken up bay Hiberno-Norman Lords outside the Pale, both for material gain, and as a means for projecting power.

Less than 150 years had elapsed since the Normans had arrived. Only a century had passed since the first Norman and English settlers had become fixtures of life in West Kerry. In the far southwest, at the extreme end of the Corca Dubhuine peninsula, the le Fureter family had been established for this century. First granted lands by the de Marisco family, the Le Fureters, now styled Fyreter, were chiefs under the Desmond FitzGeralds. They held much of Ossurys cantred – the parishes of Marhin, Dunurling, and part of Dunquin, as well as the Blasket Islands as freeholders under the Earl, lands held by the family as a seigniorial freehold or chiefry since the arrival of Walter le Fureter three and more generations before. .

The chief man of the family during the first quarter of the 14th century, Philip le Fureter junior was growing old by 1330s. In his time, Philip had been an prominent figure in the activities of the area, as documented via a number of legal references, which have him involved in various lawsuits, a hanging, a swordfight with a tenant, and finally as an appointee to a commission investigating misappropriation of private property by the sheriff. Philip is notable not simply by the varied nature of his actions, but by his clear compliance with English Law.

One may easily imagine that the man who appears as the next family head within the record may have become a bit more Irish, and a bit less English. As the cadet lines of the neighboring FitzGerald families were rapidly assuming Irish ways, one must imagine that so did Nicholas Fyreter, born c1320. As this man became the family chief, he may be placed as Philip le Fureter’s son, albeit along with every other father-to-son relationship during this period, there are no documents to confirm this. Nicholas’ appearance within the historical record as family head makes the likelihood of patrimony probable.

As a young man, this Nicholas may have preferred the Irish manner of speaking his name, “Nioclas”, probably spoke Irish as his primary tongue, and dressed in the Irish manner. During his father’s and grandfather’s times, a man may have taken pride in his “Englishry”, but with the generation of Nicholas, and far from the Pale, the young men of English and Norman descent were looking and acting more like the Irish every year.

As the Fyreters held their lands of the Earl, the family was subject to military service. During the turbulent 14th century, there may have been many occasions where some service under arms was required of these men. The strongly held affections and connections between Fyreter and FitzGerald mandated this, beyond the obligations that existed for them as liegemen. So, in 1335, when Sir Gilbert Broun, a principal Desmond military leader summoned a hosting for a raid on behalf of the Earl, the son of Phillip le Fureter, Nicholas Fyreter, responded. The action was to be a raid for plunder, directed at a vast manor in and around Rathkeale, an Abby in the County of Limerick.

The 1335 Raid on Rathkeale had unknown, or at best ambiguous motives. The Earl was needy – perhaps that was enough. Perhaps some difficulty existed between the FitzGerald family and the Montravers family, the latter being the absentee lords of Rathkeale. Perhaps the fact that Edward Montravers was absent, and the manor of Rathkeale thus assessed as an easy target was sufficient motivation. What we do know is that Sir Gilbert was the Earl’s man, and the Earl was always in need of more: more land, more money, more livestock.

What we also know is that when the call went out, there was a strong response from the leading men of the area.

Now, about the raid:

More so than any other type of action, the cattle raid is emblematic of traditional Irish warfare. Centuries before the arrival of any Norman, local conflicts between the Irish Chiefs and Kings consisted of tribal territorial incursions with the primary objective being the taking of plunder and hostages. The cattle raid occurred on many scales – from that of an individual stealing a single cow, to small armies of men sweeping an entire region clear of livestock. During a cattle raid, actual combat would most often take the form of running skirmishes between raiding parties and defenders, with pitched battles fought only when the raiders became trapped, or when the defenders made a protective stand.

An (a) dismounted Man-at-Arms and (b) a Kern

The 17 men who rode on the raid on Rathkeale in 1335 comprised a fairly strong raiding party. For each of the mounted men, there would have been a half dozen or so kern, or foot soldiers, lightly armed and fleet of foot, and quite probably native Irish. So the entire party would have comprised upward of 100 men. The mounted soldiers would have been armed with swords and lances, while the kerne typically would have carried several throwing darts (short spears) and their long knives or “skean”. While the mounted men dealt with combat, the principal function of the kern once the plunder was secured, was to drive the livestock back home.

Page from the “Unpublished Plea Roll” 9 Edw III (N.A.I., Dublin)

As Sir Gilbert made his home in the Ballyheigue area, along the coast north and west of Tralee, and as the record identifies him as having outfitted the crew, the gathering probably took place near or at his stronghold. This meant that the Corca Dubhuine men had already travelled for two days or so before the host gathered. From the legal record, we know the names of these men, and by knowing their names, we can place most of them as being Kerrymen, and several as men of Corca Dubhuine:

John FitzGalfrid

John Loveshot

William Poynaunt

William FitzPhilip Trant

Robert Trant

Andrew Og Broun

Nicholas Hussee

William FitzMathew of Ossurys

Nicholas Fyreter

Maurice Roth’ FitzMathew

William Stakepol

Richard FitzAlexander of Kerry

Thomas FitzThomas of Kerry

John FitzMathew of Kerry

Galfrid FitzRobert FitzThomas

Nicholas FitzThomas FitzRobert FitzThomas

Mathew Craddock

Given the naming practices of the time, identifying most if not all of the “Fitz’s” as Geraldine men is no doubt safe. It is interesting to note how cumbersome some of the Geraldine names were becoming by the mid-1300s – here you have poor Nicholas FitzThomas stringing out three generations beyond his own! Not surprisingly, within another few generations, fixed surnames were the practice, even amongs the lineage conscious Geraldine families.

Having mustered somewhere near Ballyheigue, these men and their kern set off towards the east, with Rathkeale their target. At this time in Munster, roads would have been lacking. One might easily surmise that between Tralee and Limerick, some sort of beaten path existed, but only as one approached the environs of a city would the tracks become more formalized and recognizable as roads. The Irish were never road builders, nor were the Normans to any great extent, and this region was far beyond the English Pale.

The Slieve Loughra mountains stood as the principal topographical obstacle along the route. Certainly these low but rugged hills were wild and difficult. Once over the mountains, the party would have moved quickly and as unobtrusively as possible. In a cattle raid, surprise was a key ingredient of success.

Perhaps they travelled only by night. Once over the Slieve Loughra, travelling in the dark for concealment made sense. Th trip would have taken two or three days, limited by the speed that the kern could make, and the difficulty of the terrain. That they rested as close to their destination as possible again is likely, and such a rest – within striking distance of Rathkeale would have been during the day, for as we know:

We have no account regarding casualties, or even if there was a fight. Recall that the purpose of a cattle raid was not to inflict death, injury, or random destruction, (those things were incidental, and not at all desirable), but to take plunder.

We do have an accounting of the plunder taken, and as noted on the plea roll, the take was considerable – over 700 animals, and a large amount of textile material. Given the handwork intensive nature of textile production during the medieval period, the value of the linen and wollen material must have been considerable.

Returning to West Kerry with such a haul would have been onerous, indeed. An additional problem with bringing such a large herd of animals back across the Slieve Lougher would be the increased probability that pursuers might catch up with them, and either recover the loot, or force a battle. There are several aspects of the situation to consider. One, if they were acting on behalf of the Earl, as might well have been the case, a principal Desmond stronghold existed at Askeaton, a fairly short march north, on the baks of the Shannon estuary, near the border of Limerick and Kerry. Askeaton may well have been their destination.Two, Rathkeale may have been selected as a target simply because the likelihood of pursuit was minimal. It is known that the Montravers family, which owned the monor for generations, did not reside there. The Abbey was continuously occupied by Augustinian friars, but the notion that clerics would pursue the raiders is as silly as it seems.

That justice prevailed is a matter of public record. As with many cattle raids, restitution was made to that aggrieved party. As may be read in the account on the Plea Roll, the raiding party was ordered to pay 1000 pounds in compensation. Such a sum represented a very large amount of money in those times, when gold or silver coinage was scarce, and highly valued. That said, whether or not the restitution was ever made, or ever made in full is not known. As an absentee, in difficult and turbulent times , with the authority of law waning, Edward Montravers may have had some difficulty collecting.

Curiously, several of the names of Nicholas’ companions show up on later documents of record. We know that in 1349, Robert Trant, Nicholas Hussee, John FitzMathew, all appear along with Nicholas Fyreter and Richard FitzMaurice in a call to arms. This order was placed upon the Earl of Desmond by Ralph, Baron Stafford, in the name of the king during Edward IIIs war in France. Yet later, in 1355, Nicholas appears as a manucaptor supporting William Stakepol as Sheriff of Kerry. Apparently having been on this great raid did not have a negative impact on Stakepol’s advancement.

So ends this recounting. In reading this, there exists a hope that a greater appreciation for the deep roots and deep history of the Ferriter Family may develop. From the earliest period of the Norman Incursion into West Kerry, members of the Ferriter Family appear within the context of the events in Corca Dubhuine , and although the Family only rises to the public record occasionally, enough may be seen to understand the ongoing role these people played in the region’s history.

Archived comments:

michele said...

Interesting article, the references are a great find, good work, as always, George! I once heard an Irish Historian say, that Ireland was all about cattle.

31 DECEMBER 2010 14:31

Muiris Feiritear

Maurice FitzGerald, c1180

Muiris Feiritear

(An Chéad Ainmneacha)

Analysis of Irish genealogies via examination of naming patterns is a proven and recognized practice. Persistence of certain favored family names generation to generation also has recognition as a means of evaluating common ancestry and collateral bloodlines. Given name preferences show up in different ways within many Irish and Norman-Irish from the earliest period. This investigation will attempt to use these methods in treating an aspect of Ferriter Family history.

One of the mysteries in the Ferriter Family’s history involves the nature of the relationship between Lucas na Srianta (Luke of the Bridles), and Piaras Feiritear (1), hero, poet, and by oral tradition, Lucas’ grandfather. There are no known direct documentary connections between these men, yet that this relationship existed has persisted as an oral tradition for many generations.

The given name Maurice has been long associated with all of the various branches of the FitzGerald family, (Kildare, Desmond, Lixnaw, the Knights, and all cadet lines). Maurice was not frequently used in other Irish or many other Hiberno-Norman families during the first few centuries following the Norman incursion in 1170/72 (2).

Within the le Fureter (Ferriter) Family in Kerry the earliest names on record are: Walter, Simon, Martin, Phillip, John and Richard. Later in the medieval period we see Nicholas, Thomas, and William. Nicholas has repetitive usage during the late 14th century through the 15th century. It is during the late 1500’s that the name Maurice first appears within the documentary record associated with the Ferriter Family. The first recorded Maurice Ferriter was Piaras Feiritear’s grandfather (3).

That a close relationship existed between the Ferriter Family and the FitzGeralds of Ossurys cantred in Corca Dhubhine, (the family of the Knight of Kerry) is clear. Both families held lands of the Earl of Desmond, and these lands shared common boundaries in Ossurys. Ferriter’s Castle in Ballysibble and the Knight’s stronghold at Rahinane near Ventry are an easy ride from one another, and these castles, taken with the additional FitzGerald tower house at Gallerus form a strong triangular defensive position across the end of the peninsula.

There are name related clues indicating that intermarriages happened between the two families - appearing in the correspondences between in names used by each of the families during this period (4) :

The significant evidentiary artifact to be taken from this table is the shift in names occurring pursuant to sustained close association with the Kerry FitzGeralds. Given no other evidences (geographical proximity, political affiliation, intermarriage), this data alone supports a familial connection beginning during the late 14th century. These correspondences began during the late 14th century, coeval with the arrival of the Knight of Kerry in Ossurys and extended until the time of Piaras’ father Eamon.

During the mid-1500s, the 3rd son of a seated Knight of Kerry (William McRuddery) married a Ferriter woman. The unnamed Ferriter woman who married this William McRuddery was quite likely to have been the daughter of the family chief of that time.(5)

One may also conjecture that Maurice’s mother was of the Knight’s extended family, which would account for the introduction of the forename Maurice at that time.

All of this data taken together illuminates the likely social and familial bonds connecting these two families at the onset of the Elizabethan era, as well as highlighting the early significance of the name Maurice, when introduced into the Ferriter lineage.

As previously noted, Piaras’ grandfather Maurice appears as the first Maurice Ferriter of record. The evidences presented support that Maurice’s name came from some association with the family of the Knight of Kerry. The second Maurice Ferriter appears during the following century in a succession of references and in circumstances that suggest that this Maurice could have been Piaras Feiritear’s son. Although no documentary evidence making the father to son connection has been uncovered, the second Maurice does appear within the record as follows :

From: “A List of Claims…Chichester House, 1700”, “A Chiefry of 10s per annum by deed dated 2nd of June, 1684, from Maurice and Elizabeth Ferriter”

From: “King James’s Army List” (D’Alton), “Regiments of Infantry, McEllicotts, Ensigns, Maurice Ferriter”, (1688 – 1690)

From: “List of Persons Outlawed for Foreign Treason”, 1699 (TCD MS N.1.3), “Maurice Feritter, Ballynehigg, gent.”

This man may have been Piaras Feiritear’s son.

This second Maurice would have been born during the War of the Catholic Confederacy, during the quiet period in West Kerry that followed the siege of Tralee (1642) and that persisted until the arrival in the region of Cromwell’s armies (1651) (6). Piaras was in Kerry and available for a second marriage at this time, given the death of his first wife early in the 1640s. Taking a second wife upon the death of a first was common practice at this time (7).

Would Piaras have been likely to have had a second marriage? Certainly. Would Piaras have been likely to have had a son born into a second marriage. Certainly. Would Piaras have been likely to have named a son born into a second marriage Maurice, as his grandfather had been named? Certainly.

For Piaras, connecting his family to the pre-Elizabethan Irish past – the past of his grandfather’s time and earlier – may have been important. Certainly we can see in his poetry an understanding of that lost era, and sadness in its passing. (8) The Norman name Maurice would have been rich with personal and historical meaning for Piaras. This name was seemingly likely to have been chosen by Piaras, and may be regarded as a supporting argument in any discussion of the lineage of Maurice of Ballynehigg, and consequently that of Lucais na Srianta.

At this point in this investigation, speculation, and discussion, it is worthwhile to examine what was happening within Ireland during this time. When Piaras’ conjectural son Maurice was born, conflict existed, with an uncertain outcome. At the end of this Maurice’s life, Catholicism and the Catholic leadership had failed politically and militarily. The Protestant Ascendancy was rapidly gaining traction, and the Penal Laws were in place. (9)

Maurice did not choose conversion or assimilation. Perhaps with less to lose in the material sense, but certainly acknowledging the sacrifice of any possible material or social gain, he held to his faith, and to his Irishness. Maurice was attainted for “foreign treason’ following the Jacobite wars, and no record has been found suggesting that he was later pardoned or restored to good standing. Maurice was outlawed. Outlawry at the time was a tool to force enemies of the crown into a “non-person” status. An individual, once outlawed, had no legal status or protection.

Tradition has this Maurice with at least one son, known as Lucas na Srianta (Luke the Restrained, or Luke of the Bridles). (10) Using the oral genealogy compiled by Padraig Feiritear during the late 1800s, we can deduce that Lucas must have been born in the late 1600s, concurrent with Maurice’s residence upon lands in the Ballyferriter area.(11) Lucas became the patriarch of perhaps all Ferriters alive today, through his two sons, Seamus Lucais (James Luke), and Sean Lucais (John Luke). Both Seamus Lucais and Sean Lucais named one of their sons Maurice. The most likely explanation for each man naming a son Maurice is that they were naming their sons after their grandfather.(12 )

Using onomastic information taken solely from the Padraig Feiritear oral genealogy, we find that by the fourth generation following these two Maurices, the name had been used at least seventeen times in individual lines of descent in Ireland. Additional Maurice Ferriters are found in U.S. Ferriter families of the period. The persistence and proliferation of this name in such a way, during the darkest years of the Penal Laws and the advent of famine times is astonishing. To this day, Maurice, the Irish Muiris, and the modern spelling variants Morris and Morrice remain alive and actively used in Ferriter lineages.

Was Maurice Ferriter Piaras Feiritear’s son? Was Lucais na Srianta Maurice Ferriter’s son? As stated, at present we have absolutely no documentary proof in answer to either of these two things.

When illuminating a history with scant direct documentation, every element of the surrounding historical context – every evidentiary artifact – must be examined for connections and insight. As detailed within this essay, significant evidence exists supporting a positive answer to both the questions posed above. In shaping an affirmative response to either of the questions, the name Maurice emerges as a meaningful common element.

So, Was the Maurice Ferriter of the late 1600s the son of Piaras? Probably. Was Lucas na Srianta likely to have been this Maurice’s son? Also Probable. (13)

NOTES

(1) That Piaras Feiritear had at least two sons and a daughter is not disputed. These sons were born early enough such that both fought during the War of the Irish Confederacy (War Against Parliament) and both are known to have taken exile to fight on in Europe after the fall of Ross Castle in 1652. The eldest of these sons, Dominick, bears a given name not seen in any early documented reference involving Ferriters, but the name Dominick is known to have been used as a forename within the Trant family. Certain evidences exist that suggest Dominick’s mother was a Trant. There may also be a connection with the Dominican Order, active in Ireland and Spain in educating Irish Catholics during this period.

The forename Dominick persisted in use within the Ferriter Family for three generations, while the name Pierce, (Piaras, Pierse, Perse), persisted in alternating generations across five generations (c1600 – c1710) in this branch of the family. Both names then disappear, and are not known to have returned in use until the 20th century.

(2) Within the 14th and 15th century manuscripts included as parts of the “Red Book of Ormond” there are documented many Norman, Wesh, and Irish names. The name Maurice does not appear at all as a forename, and only once in a Latin surname context: FitzMaurice, i.e., “fil. Mauricii”.

Recognizing that the ruling family of Ormonde, Butler, was the mortal enemy of the FitzGeralds diminishes the novelty of this data, yet still the information still makes a statement regarding usage of Maurice in Ireland outside of FitzGerald associations.

In Irish translations of the Norman “Maurice”, we find the name “Muiris”. This occurs repeatedly in the historical record. A possibility exists that an earlier traditional Irish name also became “Muiris” – that name is not connected to the Norman-Irish families discussed here.

(3) Maurice is known to have died at the end of the Desmond Rebellion, in 1584, when his son Eamon, (Piaras’ father) was 16 years old. With Eamon’s birth year understood to be 1568, our first Maurice probably was born c1530 to c1540. When this Maurice was born, the late Knight of Kerry had also been named Maurice.

(4) The Hiberno-Norman families in Munster made a practice of marrying within the local “Old English” community, and within the local Irish communities for property gain, and for security. Family alliances were socially and politically important. Although the scanty documented history as presently known cannot confirm the names of many wives, we do know that in the mid-1500s the third son of a seated Knight of Kerry (William “McRuddery”) did marry a Ferriter woman.

(5) The known dates associated with “The Ferriter” Maurice, and those of William McRuddery indicate the possibility that this lady was Maurice Ferriter’s sister. Given Maurice’s standing as family chief, and the likelihood that the seated Knight would be seeking family alliances, if Maurice had a sister, she would have been the candidate for marriage into the knight’s family. If McRuddery’s wife was not Maurice’s sister, she was very certainly his close blood relation.

(6) Born during the years 1645 – 1650, Maurice was likely to have been a married man during the property transactions of 1684, a junior officer in his prime during the Jacobite Wars of 1688 to 1691, and a high profile (by name) papist as the Penal Laws came into effect at the close of the 17th century.

(7) The likelihood that Piaras had a second wife, and that she was of the Moriarty family is almost conclusive. Piaras is referred to in the Runincinni Commentaries as being the brother-in-law of Thadeus Moriarty, the Prior of Tralee (also executed in 1653), and in at least one source as being the son-in-law of Dermot Moriarty (Dermot O’Dingle) who was a Moriarty Family chief of the time.

(8) In addition, the name Maurice would commemorate not just his grandfather, but the late Maurice FitzGerald, the Knight of Kerry’s brother in whose memory Piaras had written a “caoine” (keen) that has been one of his most enduring pieces of poetry. Similarly, the name provides a connection to Maurice FitzGerald of the Desmond FitzGeralds, uncle of the last Earl, father of James FitzMaurice the great hero of the Munster Catholics during his grandfather’s time. All of these things are concrete contributing reasons for Piaras to use this name for his son.

(9) Piaras’ eldest son, (Dominick), and his heirs were moving in the direction of establishing English credentials, a process that eventually led these people into accepting Protestantism, and into a struggle to maintain status as gentry. This branch of the family became extinct in the male line by 1865.

(10) Tradition alone – as discussed, there are no direct documentary evidences. There are other Ferriter males in the historical record who are in the line of Dominick, and one other who may have been Maurice’s brother. Given the known rarity of the Ferriter name during the post-Elizabethan era, (Piaras quite possibly was the sole inheritor of the name at that time), that Maurice was Piaras’ son seems likely. There are no documentary evidences of any other Ferriter male of this period producing offspring. Similarly, with Dominick’s offspring well documented, other Ferriters emerging during this period are likely to have been of the line of Maurice.

(11) Based upon the earliest birthdates on the Feiritear chart (1808, 1809, 1811, occurring in the 5th generation), and using a 30 year (+/- 10y) generational span, Lucas would have been born c1680 –c1700, which fits correctly with what is known about Maurice, who would have been born just prior to 1650).

(12) The name Lucas was also used by each of these men in naming sons, which is very strong evidence that they were Lucas’s sons, as well as Maurice’s grandsons.

(13) While this essay may not be considered conclusive, the arguments presented in support of the possibility that Maurice was Piaras’ son are persuasive. The name Maurice was not just a random selection or even simply a tie to the past or a link to lineage, but was a symbol of the choice of constancy with tradition, faith, and heritage. Maurice is an honorable name, and an honor bestowed upon those who bear it. For us, the name continues to include all of the history, plus the additional merit of long usage within the family – the memory of all those who have borne this name before. Finally, for those interested in such things, the name Maurice becomes another item of evidence to use in closing a gap in the Ferriter Family narrative.

More about seoirse

George Edmond Ferriter

From a branch of the Ferriter family that made its way to Illinois and Iowa during the middle part of the 19th century, George is a resident of Doylestown in the state of Wisonsin, USA. His was a family group that, while scattered, developed a tradition of keeping the family history alive in a sort of oral tradition. George has had a lifelong interest in Ferriter family history, both the history of the family in Ireland and of the traveling branches. He has written many short blog pieces of Seoirse Feiritear, and has presented at earlier Ferriter events on several topics. In 2015, George will make a presentation on Ferriters who served in the US Civil War. This will focus on the individuals, but also on the larger context of the Irish in this conflict. Extending from a military line, George is a veteran of the US Air Force. George's grandfather John Patrick Ferriter, and his father Charles Arthur Ferriter were career military men as veterans of WWI and WWII respectively. A retired engineer, George currently serves as Village President in Doylestown.